A degraded riparian zone is often entirely mowed, which results in bare soil along a stream bank. A lack of vegetation is a visible and primary variable that relates to overall riparian health. A degraded riparian area does not provide the important functions and services of a healthy riparian zone (see riparian function FAQ).

A heavily mowed, channelized creek exhibiting degraded riparian health.

Probably the most important driver of degradation to a riparian zone is the alteration of the natural hydrologic cycle that occurs from the urbanization of a watershed. This change or degradation in rain infiltration, flashy flows and baseflow essentially disconnects the banks and buffers from the stream and the water table. The types of vegetation that thrive in wet, active floodplains cannot survive in this disconnected state and the result is a degraded, abandoned, or upland vegetative community.

Changes that occur to riparian hydrology through urbanization (from Groffman et al. 2003. Down by the riverside: Urban riparian ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment 6:315-321.)

After hydrology, the next most important factor that degrades riparian areas is alteration of the mature vegetative communities that evolve in these areas. This occurs primarily via human intervention, i.e. mowing, agriculture, logging or development. These activities remove the original vegetation, and degrade and compact the soil. These activities, when repeated over decades, make it very difficult to “replant” a healthy riparian vegetative community. Removing the disturbance that is keeping the riparian area in a degraded state is the most important thing to do in riparian restoration.

A trail area in a park where soil is compacted and vegetation is excluded.

The Department has considered how these Grow Zones affect flooding. Our engineers have determined if floodplains will increase with the anticipated fully grown out vegetation. The Grow Zone projects will not increase flooding on private property or public roadways.

A “Grow Zone” is an effort to halt mowing along streams and allow the growth of more dense, diverse riparian vegetation. This improves water quality, lessens erosion, increases wildlife habitat, and provides other ecosystem services. It is our hope that Austinites will embrace these changes and appreciate the benefits of natural stream corridors. If you or your group is interested in getting involved please check out the options under the FAQ “What can I do?”

A “Grow Zone” is an effort to halt mowing along streams and allow the growth of more dense, diverse riparian vegetation. This improves water quality, lessens erosion, increases wildlife habitat, and provides other ecosystem services. It is our hope that Austinites will embrace these changes and appreciate the benefits of natural stream corridors. If you or your group is interested in getting involved please check out the options under the FAQ “What can I do?”

Participate

Click here to be notified about volunteer workdays along Grow Zones.

Several organizations in the local area, such as, Keep Austin Beautiful and the Austin Park Foundation coordinate volunteers to care for our natural areas. Pitch in to be part of the solution by adopting a creek or participating in It’s My Park Day!

A few local volunteer organizations that have been trained by WPD to self-lead some restoration techniques in Grow Zones follow this maintenance schedule.

If you would like to propose a volunteer project in a Grow Zone please use this form to make the request.

Help keep the riparian zone clean

Pick up trash and remove pet waste to enhance both the environment and our enjoyment of natural areas. Every time someone puts garbage in the appropriate waste receptacle, it is silently appreciated by those who never see the trash on the streets and in our creeks. www.LetsCanItAustin.org

Give positive feedback to Park officials

Positive feedback is always appreciated and helps provide encouragement for programs that seek to protect and restore natural areas.

Participate

Several organizations in the local area, such as, Keep Austin Beautiful and the Austin Park Foundation coordinate volunteers to care for our natural areas. Pitch in to be part of the solution by adopting a creek or participating in It’s My Park Day!

Restore the area you control

Evaluate the area that surrounds your home and help your personal environment become a functioning part of the greater environment. The City of Austin’s Grow Green program is a great place to start learning about plant selection to promote native Texas plants that provide benefits to wildlife such as butterflies and birds. You can even create a “Backyard Habitat” that can be certified by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

If you live near a creek download our Creekside Homeowners Landscape Design Template.

Spread the word and shift the paradigm

In this increasingly urbanized area, our connection to nature is growing further and further apart. Communication will play a key role in turning our collective thoughts back to understanding the importance of nature. Tell a friend what you know and you’ve already doubled the effort.

Observe, learn and enjoy

Inspire the naturalist in you to learn the names, habits and functions of the plants and wildlife in our area. A fantastic way to appreciate nature is to take the time to observe it and learn about the extraordinary web of interactions that make natural riparian systems function.

Adopt-a-Creek groups who have an adopted creek section that’s a Grow Zone are encouraged to monitor the area. They select a 300-foot stream segment that best represents the area and conduct annual monitoring of the same sample plots over time. Monitoring takes place within the same month every year to capture long-term restoration progress. Click here to download the Citizen Riparian Monitoring Protocol.

Riparian zones can support plants that are unable to exist anywhere else. These plants in turn help to keep the riparian zone healthy and functioning properly. A plant guide for creekside residents can be found at Grow Green’s Creekside Homeowners Landscape Design Template , for a more general streamside restoration plant list check the Riparian Template. It is important to remember that healthy riparian vegetation can look shaggy and overgrown as it transitions into a mature woodland.

Download our Wetland Plants Field Guide (Web Friendly 7.8MB - High Resolution for printing 238.4MB) to learn more about plants seen in Central Texas creeks and wetlands.

Click here to see a video about how to plant bare root seedlings.

Ready, Set, Plant! is a partnership between the City of Austin Parks and Recreation Department’s Forestry Division, City of Austin Watershed Protection Department and local non-profit TreeFolks, Inc. to plant small native tree seedlings that will not require irrigation. Planting seedlings will enable us to restore native tree and shrub diversity during drought as well as retain water and improve water quality in Austin’s waterways.

Click here to download this restoration techinque's management guide for Removal of Invasive Trees- Weed Wrenching and Girdling.

Click here to download the volunteer restoration plan template. If you have any questions about developing a riparian restoration plan, please contact John Clement or Ana Gonzalez.

Click here to download this restoration technique's management guidefor volunteer leaders.

Ragweed is a native plant that maybe perceived as undesirable on stream banks. It has some benefits such as reducing the effects of direct sunlight on the soil and it likely reduces soil compaction while increasing soil moisture and organic matter. However, when ragweed growth is very dense it may slow down the establishment of other desirable species. In these cases ragweed stems can be bent at the beginning of their flowering stage in the fall. This technique gives other native plants a better chance of growing while maintaining the benefits that ragweed provides to the soil.

Maintenance Schedule (for local groups training by WPD in self-led restoration techniques)

Volunteer info

Profile, age range - appropriate for 10+ years old, with adult supervision

Clothes and safety - Closed toed shoes, long sleeved shirt, pants, individuals who are sensitive to allergens should also wear goggles and a mask

Click here to download this restoration technique’s management guide for volunteer leaders

Click here to download this restoration technique's management guide for volunteer leaders.

Click here to download this restoration technique's management guide for volunteer leaders.

Seed balls are marble sized mixtures of compost, clay, native seeds, and water. They are a cost effective, low maintenance method of re-vegetation which requires little water. Seed balls are scattered directly onto ground and not planted.

- Thoroughly mix dry clay (3 parts), compost (2 parts), and seed mix (1 part) specific for the light/moisture conditions of the site.

- Sprinkle with water until mixture sticks/binds together like cookie dough.

- Take a pinch of the finished mixture and roll (in the palm of your hand) into marble-sized round balls

- ‘throw’ or spread the seed balls within the Grow Zone or add them by coir logs

Maintenance Schedule (for local groups training by WPD in self-led restoration techniques)

Volunteer info

Profile, age range - appropriate for 5+ years old, with adult supervision

Clothes and safety - closed toed shoes.

Provided by Watershed Protection Department for official Grow Zones: Seed Mixes, clay, compost

Click here to download this restoration techinque's management guide for volunteer leaders .

This technique must only be done with WPD staff present or with a non-profit that has had direct training on the technique from WPD scientists. Click here to learn more about techniques used by WPD staff.

Maintenance Schedule (for local groups training by WPD in self-led restoration techniques)

Click here to download this restoration technique's management guide for volunteer leaders.

Plants help improve water quality and anchor soil. While soil is the foundation for plants, without roots to stabilize the soil, bare soil washes into our creeks whenever it rains. Seeds germination rates improve when there is good seed to soil contact.

- Rake the ground to loosen the soil.

- Spread seeds over the soil at the rate of 30lbs per acre.

- Press the seeds in to the ground.

Maintenance Schedule (for local groups training by WPD in self-led restoration techniques)

Volunteer info

Profile, age range - appropriate for 5+ years old, with adult supervision

Clothes and safety - Closed toed shoes, workgloves

Other tools needed - rakes

Provided by Watershed Protection Department for official Grow Zones: Seed mixes

It’s simple- the first step is to stop mowing along the stream edge, allowing vegetation to grow back naturally. While appropriate in some areas for public access and recreation, repeated mowing along the stream bank is not conducive to a healthy riparian zone and creek.

There will be a riparian buffer at least 25 ft wide on each side of the creek, with a variety of plant heights and thicknesses, and frequent open view corridors between 3’ and 7’.

Ecosystem function can be defined as all of the processes necessary to preserve and create goods or services valued by humans. Healthy functioning riparian zones:

- Improves the natural and beneficial functions of the floodplain

- Prevents stream bank erosion

- Filters storm runoff, removing pollutants before they reach the creek

- Provides habitat and food for a diverse group of animals

- Provides shade that cools air and water temperatures

- Creates a greenbelt forest with diverse tree and plant communities for outdoor enthusiasts

- Reduces the City’s carbon footprint

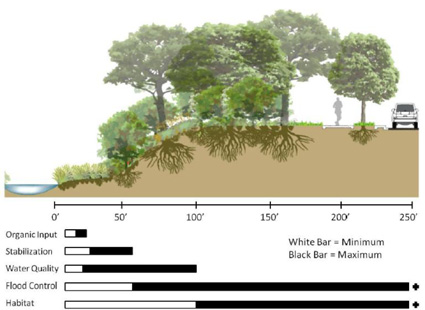

Riparian zone restoration attempts to restore the natural process necessary to maintain a high level of ecosystem function. In general, the larger the riparian buffer the more ecosystem functions it can provide.

This image shows the various buffer widths associated with riparian zone function. Organic inputs into the stream are important sources of nutrients and habitat (width 15-25 ft). Stream stabilization is maintained by riparian vegetation (width 30-60 ft). Water quality is the ability of the vegetation to intercept runoff, retain sediments, remove pollutants, and promote groundwater recharge (width 20-100 ft). Flood control is the ability for the floodplain to intercept water and reduce peak flows (width 60- 500 ft). Riparian habitat is the ability of the buffer to support diverse vegetation and provide food and shelter for riparian and aquatic wildlife (width 100-1500 ft).

RIPARIAN ZONE RESTORATION METHODS

There are three generalized approaches to restoring a disturbed riparian environment:

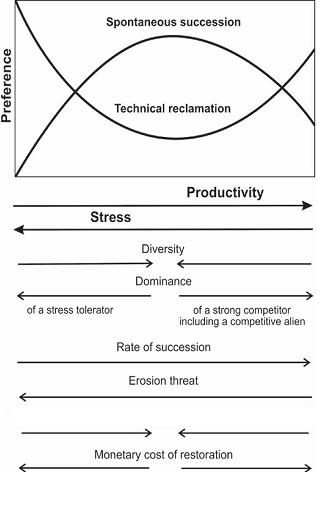

(1) rely completely on passive (spontaneous succession)

(2) exclusively adopt active, technical measures

(3) or a combination of both passive and active techniques toward a target goal (Hobbs and Prach 2008). Passively restored sites exhibit robust biota better adapted to site conditions with increased natural value and wildlife habitat than do actively restored sites (Hobbs and Prach 2008).

Passive restoration requires minimal management and is more cost effective than alternative methods. However, passive restoration is often the slower approach and is more dependent on adjacent site conditions. When relying on spontaneous succession the vegetation community of adjacent sites, an approximate 100 meter distance from the disturbed site, is critical for successful restoration (Hobbs and Prach 2008). In general, passive restoration that relies on spontaneous succession should be employed when environmental disturbance is not very extreme (Figure 1) and no negative results (erosion, water contamination, negative aesthetic perception, etc…) are foreseen (Hobbs and Prach 2008). When site productivity and stress are extremely high or low, active (technical reclamation) may be necessary (Figure 1). The persistence of undesirable functional states is an indication that the system may be stuck and will require active intervention to move it to a more desirable state (Hobbs and Prach 2008). Understanding when passive versus active restoration approaches are warranted can increase chances of success and reduced project costs.

Passively restored sites exhibit robust biota better adapted to site conditions with increased natural value and wildlife habitat than do actively restored sites (Hobbs and Prach 2008). Passive restoration requires minimal management and is more cost effective than alternative methods. However, passive restoration is often the slower approach and is more dependent on adjacent site conditions. When relying on spontaneous succession the vegetation community of adjacent sites, an approximate 100 meter distance from the disturbed site, is critical for successful restoration (Hobbs and Prach 2008). In general, passive restoration that relies on spontaneous succession should be employed when environmental disturbance is not very extreme (Figure 1) and no negative results (erosion, water contamination, negative aesthetic perception, etc…) are foreseen (Hobbs and Prach 2008). When site productivity and stress are extremely high or low, active (technical reclamation) may be necessary (Figure 1). The persistence of undesirable functional states is an indication that the system may be stuck and will require active intervention to move it to a more desirable state (Hobbs and Prach 2008). Understanding when passive versus active restoration approaches are warranted can increase chances of success and reduced project costs.

Establishing a buffer, with its mix of grasses, forbs/wildflowers, shrubs and trees, allows for a variety of benefits to the surrounding ecosystem:

- Filters pollutants out of storm runoff before it reaches the creek

- Limits erosion, protects creek banks and keeps sediment out of the creek

- Provides shade and maintains moderate water temperatures

- Provides habitat for a diverse group of animals, both on land and in the water

Trash in waterways is an unfortunate byproduct of society. Whether intentional or accidental, most trash that is dropped on the ground ends up in our streams and river. There are a variety of options for cleaning it up. The City of Austin assesses trash quantity using a visual assessment to evaluate severity. Streamside vegetation has the ability to capture trash floating in the streams, preventing it from going downstream to the Colorado River and Gulf of Mexico. The City of Austin does perform some trash clean-up but the problem is so extensive that it is impossible to keep all waterways free of trash. In order to better clean our streams it takes the whole community to take part. For this reason Keep Austin Beautiful assists Austinites with supplies and support for cleanups. If large trash such as furniture, appliances, and vehicles are in the stream please call 311 to report it.

What are the vegetative stages of riparian restoration?

Allowing a mowed stream and riparian zone to return to a natural state can take a while. Remember a forest can be cut down in a day but it takes a generation of care for it to return.

A variety of wildflowers are dominant during different seasons.

Grasses begin to grow taller, protecting the soil from the sun and forming a rich organic layer.

Tree saplings grow in abundance taking advantage of the full sun.

Years after the mowing ends the riparian zone reaches maturity.

There will be a riparian buffer at least 25 ft wide on each side of the creek, with a variety of plant heights and thicknesses, and frequent open view corridors between 3’ and 7’.

Society for Ecological Restoration

TPWD Managing Riparian Habitats for Wildlife

City of Austin Short Reports

SR-12-15- Live Staking in Riparian Restoration Projects

SR-12-13- Riparian Restoration Prioritization Methodology

SR-12-12- Riparian Functional Assessment

SR-12-11-Sapling Survival Assessment

SR-12-05 Functional approach to riparian restoration

SR-11-13 Riparian Reference Condition

SR-04-09-Development of Riparian Index

It’s happening all over Austin!!

The Watershed Protection Department and Parks and Recreation Department are working together to improve riparian areas in some City parks.

Click here for a map of the sites.

Click on the park name below to see a fact sheet describing the specific efforts at that park .

Big Stacy Park, Blunn Creek Greenbelt

Commons Ford Ranch Metropolitan Park

Shoal Creek Greenbelt at Allendale

Willowbrook Reach on Boggy Creek

Urban wildlife, or “backyard wildlife” is often limited in diversity, however by allowing an area to grow naturally, and reducing the urban characteristics this limitation can be reduced. Diversity of plants and increased layering, or structuring of plant types can provide the food and habitat for many of the animals that naturalists enjoy such as birds, butterflies, mammals, reptiles and a myriad of small critters.

Birds

Riparian corridors and adjacent woodlands can provide outstanding habitat for birds, both resident and migrating. Depending on the structure, diversity and health of the vegetation in the corridor, an amazing number of birds can be found here.

- Chickadees, mockingbirds, warblers, vireos, woodpeckers, titmice, sparrows, towhees, flycatchers, blue jays and wrens, depend on the wealth of insects that live on the grasses, forbs, wildflowers, shrubs and trees.

- Cardinals, dove, goldfinch, junco, and cedar waxwing gleam and important part of their diet from seed and berry producing shrubs.

- Hummingbirds drink nectar from some flower-bearing plants and small trees.

- Eastern screech owls, barred owls, and sharp-shinned hawks, and other predatory birds use wooded areas for their homes and hunting ground.

Butterflies

New leaves in the spring and early summer provide the critical food for the caterpillars that become moths and butterflies. Flowers from forbs, shrubs and trees provide nectar to many resident and migrating butterflies. Often caterpillars will only eat a certain type of plant (this is called host-specific relationship) so an increase in the diversity of plants will increase the diversity of butterflies.

- Skippers, satyrs, wood-nymphs eat grasses and sedges as caterpillars.

- Swallowtails eat some tree leaves especially citrus, black cherry and willow in addition to herbs such as relatives of dill, parsley and carrot.

- Monarchs and queens eat milkweeds and milkweed vines.

- Whites and sulphurs eat relatives of the mustard and legume

- Admirals, viceroy, sisters and morning cloak eat tree leaves, especially willows.

- Painted lady and red admirals prefer thistles and nettles.

- Great purple hairstreak eat mistletoe while other hairstreaks prefer legumes and mallows.

- Heliconians and fritillaries eat members of the passion-vine family.

Reptiles

Reptiles are a fascinating and beneficial part of riparian function. The vast majority of reptiles are harmless, and we only have four venomous species in Austin. Common harmless reptiles include:

- Gulf Coast toads thrive in riparian woodlands with loose soil, thick leave litter, shade and access to insects for food.

- Rough earth snake is a very small harmless snake that lives in the soil and leaf litter eating earth worms and slugs, and the non-venomous Texas rat snake helps control the rodent population.

- Red-eared slider and common snapping turtles must crawl out of the creek to lay eggs in the loose soil of the upper banks in the riparian corridor.

- Skinks are small lizards that live in leaf litter and eat insects

- Anoles are medium sized green/brown lizards that are sometimes mistaken for chameleons.

Mammals

The big winner of an improved riparian corridor is our ever-present fox-squirrel, however, the possibility remains for other native mammals to pass through if the corridor is wide enough and long enough.

- Fox-squirrels are frequent residents of parks and woodlands and primarily live in the trees.

- Grey squirrel (aka “rock squirrel”) are less often seen ground squirrels in steep hilly areas that burrow in the soil.

- Armadillos are crepuscular and nocturnal and may occasionally be found rooting around the loose soils and leaf litter in large riparian corridors.

- Grey fox are primarily nocturnal and usually stick to woodland areas that are undisturbed.

Small critters in the leaf litter

A myriad of small invertebrates live in the loose soil and leaf litter. They may be considered to be the most important animals since they often play a vital role in turning dead vegetation into soil and organic matter which plants need. These include crickets, earthworms, fly larvae, snails, slugs, beetles, etc. These small critters are also the primary food source for many of the insect-eating animals mentioned above.