Net-Zero Hero: Chiara "Sunshine" Beaumont

I’m helping to make Austin Net-Zero by being authentic and teaching people how to better relate to their relatives in the outdoors.

The Office of Sustainability recognizes that climate change is inextricably linked to humanity’s long history of inequality and injustice perpetuated by legacies of colonialism and slavery, based on the exploitation of people, land, and nature.

In honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we introduce our newest Net-Zero Hero: Chiara “Sunshine” Beaumont. Chiara is an Indigenous educator and resistance artist who shares her gifts across the state, organizing on behalf of Indigenous communities and Mother Earth. A member of the Karankawa Hawk Clan, she carries this lens with her through all she does.

We met with Chiara at Red Salmon Arts and the Resistencia Bookstore and traveled to Roy G. Guerrero Park to talk about her journey to this path and the advice she would share with others.

What inspired you to take action?

The path to being an Indigenous educator and resistance artist seems very niche, but it felt really straightforward to me.

I've always loved the outdoors. And I also always believed everything my mom told me. She's the reason why I'm here now. My mom is an angel that walks the Earth. She’s the best mom in the world. She is one of the first people in our lineage to have completed a successful educational career, which brought her from Texas to Virginia for better work opportunities. She took being Tejana very seriously. Everyone knew as soon as you walked into our home in Virginia that we were from Texas — that Texas was home. Part of being raised by her was that she was also saving a part of our people. She made sure to teach us that we were Karankawa. It was a point of pride for her. Whenever we’d have heritage days at school, she would remind us that we were Tejano, but specifically, we were Karankawa and had always been in Texas. She made sure that if we weren’t down in Texas with our people and our family, we were constantly being reminded that we weren’t home. She was such an inspiration. My mom told me that I could do anything — and I believed her.

I knew that I didn't really want a traditional job. For a long while, I just wanted to be a mom. And then, I wanted to be an elementary educator. When I couldn’t pass math, I decided to study art. I went to college for art, with a minor in outdoor education.

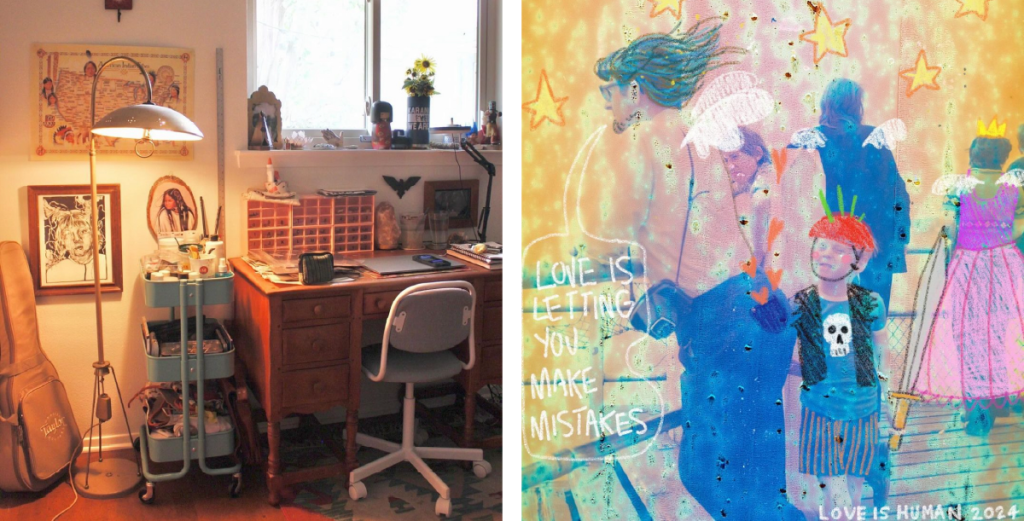

Left to right: Chiara’s art studio; a piece of art created by Chiara for the Love is Human collection.

When I graduated, I moved back to Texas and became an outdoor educator. I couldn’t help but naturally introduce Indigenous — and specifically Karankawa — idealogy into what I was teaching. I began bringing up and calling into question outdated colonial thoughts that we’ve been taught were true. I was an outdoor educator who happened to be Indigenous — people took notice and really liked what I was offering. It blossomed from there.

How did you do it?

It centers on the words that leave my mouth and the art that leaves my hands.

For the words that leave my mouth, I give classes, lectures, and workshops on what I call “decolonizing environmental activism and reconnect walks.” Through these practices, I am inviting people to listen to another perspective as it pertains to how we relate to the outdoors.

For instance, one of the biggest misconceptions — and luckily, it’s changed since the early 2010s — but there was a long-held belief that our plants compete for resources. I remember even as a child in my early science classes being taught this. They complete for water. They compete for sun. This is so colonial — and so wrong. Indigenous wisdom, knowledge, and science is now known as the truth. No one out there is competing for anything.

They’re sharing. They are sharing their life source with one another. Sometimes someone gets sick and can’t use what’s given to them. Sometimes there are people who aren’t given enough. What we know now is what Indigenous people have always known: those relatives of ours are not competing. It is only human beings who do this. We made these rules and definitions.

Chiara visits the corn being grown in front of Red Salmon Arts.

On the reconnect walks, I introduce myself and ask people when the last time was that they felt truly connected to the outdoors. I often lead these as a specialist at a health and wellness resort. I may hear things like just this morning, or two months ago, or on a recent trip to Cabo. I then share my response which is: all the time. Whether I am inside or outside, I am connected. I share a history of the land over 145 million years and how it’s changed. How Panagea broke into two, how the ocean got pulled into the Gulf of Mexico, and where we are now.

I spend the remainder of time reintroducing people to our relatives out there, mostly by sharing with them everything we have in common. Things like, ‘How do we know they’re aging? Just like you and I, their foliage is changing color. Their skin is changing texture. They’re started to lean over just like us.’

My family and I use the word “relative” because, when I was growing up, I was taught that every single living thing on this Earth was created by the Creator. And because we're all creations, we are all just as special. Nobody is on top, and nobody is on bottom — we are all on the same level. I use the word relative on purpose because, when we consider them as people, too, it becomes so much easier to maintain balance with them. It means I’m not going out to pluck every pretty flower I see because I wouldn’t want a giant to pluck me off the ground — not without at least talking to me first. We call them relatives because they do everything we can do. We have to relate to them.

I think these lessons have been so impactful because people come to realize that what I'm sharing has existed for 20,000 years. For many people, the ideas that they hold onto and are guided by have really only existed for 500 years at most. To be presented with information that has withstood the test of time is valuable and sticks with people.

Chiara points out the Palo Santo at Red Salmon Arts, a practice she does before her gatherings in the space.

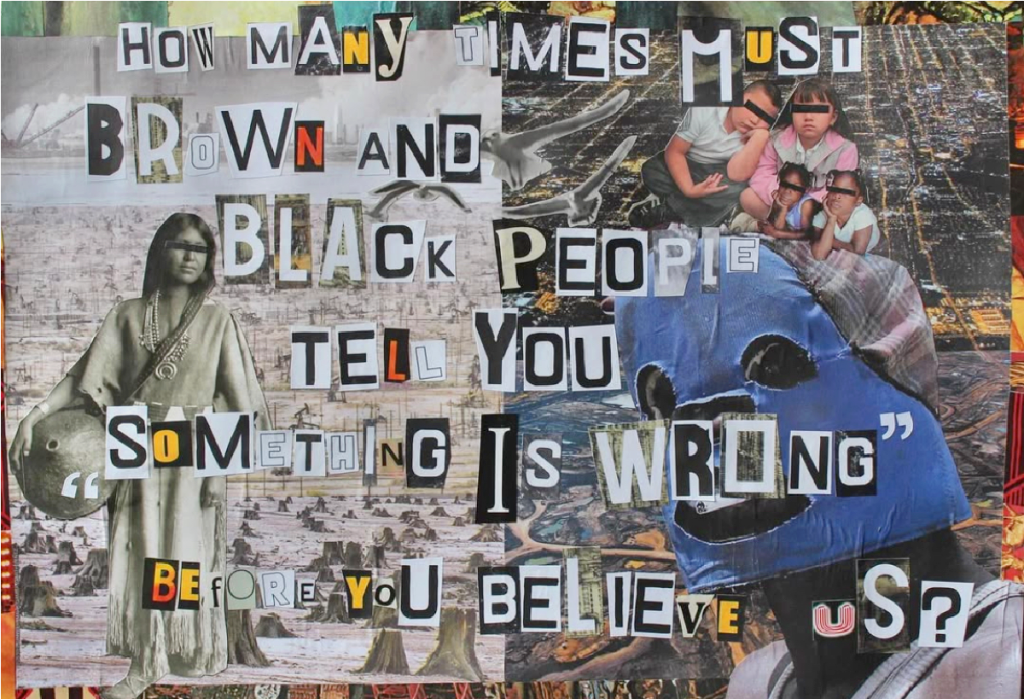

For the art that leaves my hand, my art practice is a necessary catharsis. It is a way to express pain or sadness that I’m uncomfortable or unable to express with words, actions, or music. My art is meant to reflect what it feels like to be a person on my own homelands who does not see my people. Or worse, who sees my people suffering and knows their suffering directly benefits others who either don’t know or don’t care. It is an expression of the pain involved in believing in revolution and organizing for resistance beneath settler colonial imperialism.

A selection of Chiara’s art, left to right: “Revolution Now” (collage on canvas); “At Peace Wherever I Stand” (collage on canvas); “If I’m Feeling Particularly Evil” (mixed media collage on canvas).

What's been most rewarding about getting involved in this way?

The most rewarding part is twofold.

On an ego-less level, it’s when people return to me and tell me that they haven’t looked at their backyard the same way since meeting me or going on a walk with me.

On a more self-serving level, the most rewarding part of being involved in this way is the support I find in my most vulnerable moments. There is a community around me of people who I’ve built relationships with through my lectures, classes, or the community work I do, who love me and want to help me.

Chiara walks through Circle Acre Preserve, a site where she has held healing ceremonies for the community.

What's been the toughest part?

The toughest moments are always whenever I encounter conflict within my own community and when I see my people struggling, whether at a close distance or far away. I always say that the work I do is for the future generations, so those are my people as well. Doing this work — dedicating my life and my spirit to it — is so lovely. But when it appears that there is still so much work to be done for my people, it makes me feel like it will never be enough. It can feel like it’s just too late.

There are times when I’m still unable to give the support that I so adamantly what to give. I can be doing all this work and still be seeing members of my community struggling. It feels like not enough. There’s always something much larger above us: the confines of capitalism. It keeps us down and keeps us from elevating our voices and our efforts.

But, with a smile on my face, I am cursed to continue. Whenever I feel like I’m tired or this work is pointless, I always get up and try again, because my spirit is indomitable. I have to put my trust in it, and let my spirit take me where it wants to go. It is hardest when I am questioning my spirit.

“Brown and Black Expression of Pain is a Look into White Future” (collage on paper) by Chiara.

What do you wish more people knew about Indigenous culture in Austin?

There is not one culture. Many people believe there is such a thing as ‘Native American culture,’ but there is no such thing as Native American culture, spirituality, or wisdom. That concept is incredibly homogenizing. It is a myth. Every tribe and every clan has their own culture.

There are lots of different cultures here, and all of us just happen to be Indigenous. Each of us has a specific tribe, clan, or band. Within that, we’re all very, very different. What we have in common, though, is that we have all originated from this place, and our central practice has always been to serve and protect Mother Earth and our future generations.

What do you think today's leaders could learn from Karankawa heritage and practices?

I know I just said there’s no such thing as Indigenous culture, but here I go…

For nearly any Indigenous community that exists globally, there is a very common thought taught to almost all of us: leaders should not want to be leaders. Instead, your people should be elevating you to that position.

The whole system is calling for radical liberation. I use the word ‘radical’ in the etymological sense: radicalis, from the 14th century Latin, referring to ‘from the root.’ We need reform from the root. To dig up and address the issues of what it means to be a leader. I would argue that if it’s a position that you’ve put yourself into, that’s the wrong way to go about it. You shouldn’t even want it. You need to be so far removed from ego to completely serve the people.

Chiara pauses in the Circle Acres Preserve.

Chiara pauses in the Circle Acres Preserve.

Can you talk about the space we’re in today and its significance to you?

I was first introduced to this space as a vendor at a Colectivo In Situ event for Indigenous people offering their medicines — which I use to mean their gifts. I was there with my art. Shortly after, I was looking for a space to safely host community organizing gatherings, and the staff reached out to share that Red Salmon Arts and the Resistencia Bookstore were already being used in this way. It felt like, cosmically, things were aligning. I came down to meet Andrea, one of the workers here, and learned more about their fantastic history.

The space was founded by raúlrsalinas, who called himself a Chicaindia, meaning Chicano and Indian. He knew he was Indigenous, but acknowledged that his Indigenous roots, like so many Indigenous people here in Texas, had either been lost to time or intentionally erased by the violence that was settler colonialism.

He established this space in the 1980s to make visible the invisible as it pertains to being an Indigenous person in Central Texas, especially for Chicano- and Chicana-identifying persons. He started the conversation for people to understand that if they were brown and from here, they were likely Indigenous. There’s power in that. He encouraged community to set aside conflicts by understanding what was at the root and recognizing that we are all relatives. He did a ton of work with community.

Left to right: Chiara stands at the entrance of Red Salmon Arts; a collection of media available at Red Salmon Arts’ Resistancia Bookstore.

This continues to be a space for community organizing, outreach, and support. It’s a safe harbor for a lot of people. It’s a multifaceted space meant to elevate and liberate the Indigenous person, whether they have been deeply involved in understanding their roots or they are just starting to uncover and discover what that means to them.

Is there a book, documentary, or other piece of media you would recommend for folks wanting to learn more about these topics?

I would encourage people to look at the website for Red Salmon Arts to learn more about their history and upcoming events.

The quickest way to learn more about me is to follow my Instagram page.

My people also have a website: Karankawas.com. In general, if you are trying to learn about Indigenous peoples in Austin or Texas, find websites or social media led by Indigenous people. Get your information straight from the source. We are lucky that many Indigenous folks in Central Texas have a presence on social media.

What advice do you have for others?

My advice is seriously to look into your roots and reconnect with them. Every so often, I encounter people who think it’s silly — they don’t have a reason why or they are too busy.

It is very worthwhile. Every single living thing on Mother Earth has roots to the Earth. I know where mine start — in South Texas.

Once people know where their roots start, they can truly never die. You come from the dirt and you will return to the dirt — and there is a place where you first did that. There is something really powerful about that. Everybody’s journey reconnecting to their roots will be so different, but it will also always be life-changing.

Discover the Indigenous Peoples whose lands you now reside on by visiting native-land.ca. You can learn more about Indigenous Peoples’ Day through the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. To learn more about Austin's net-zero goal and explore actions you can take to support a greener community, view the Austin Climate Equity Plan.

Share your Net-Zero contributions with us on X (formerly Twitter) or Facebook, and use #NetZeroHero. If you know a Net-Zero Hero (or heroes!) who should be recognized for their efforts, send your nomination to sustainability@austintexas.gov.