Net-Zero Hero: Warinda Harris

I’m helping to make Austin Net-Zero by advancing park equity in Austin’s under-resourced communities.

Meet our newest Net-Zero Hero, Warinda Harris! As an organizer with Central Texas Interfaith (CTI), Warinda is helping Austin communities build power, strengthen civic engagement, and advance environmental equity. Through her work on green space access and equity, Warinda has helped connect residents in East and South Austin with opportunities to shape the future of their neighborhoods. CTI has partnered with Austin Parks and Recreation, Huston-Tillotson University, and local organizations through the national People, Parks, and Power initiative to ensure that every Austin resident has safe, welcoming access to nearby nature.

Central Texas Interfaith is an affiliate of the Industrial Areas Foundation, the largest and longest-standing network of faith and community-based organizations in the country. It is a broad-based organization of congregations, public schools, worker organizations, health and legal clinics, and neighborhood associations across the five-county area that work together to address public issues that affect the well-being of our families and communities.

We met with Warinda to talk about how community organizing can drive environmental justice, how storytelling sparks policy change, and why building relationships is at the heart of a more equitable and resilient Austin.

What inspired you to take action?

During the pandemic, our leaders at CTI worked hard to stay in touch with each other and share their experiences. We have leaders from all over the area, but we found that our folks in East and South Austin were experiencing the outdoors differently from their wealthier West-side neighbors. Many of them were considered essential employees and could not work from home. They were dying at a higher rate because they were struggling to not bring COVID into their homes. They were also finding it difficult to distance outside with their families and see their neighbors at local parks because their green spaces did not have the infrastructure to support it. Our leaders saw this as an equity issue and began exploring how to engage around it.

Warinda stands in the pocket park of CTI’s most recent project.

How did you do it?

In 2022, Central Texas Interfaith became a part of the People, Parks, and Power cohort through the Prevention Institute. We’re part of a cohort of 14 organizations from around the U.S., all working on green space equity, sharing knowledge with each other, coming into community with each other, and learning from each other as we do the work. We’re part of the first national funding initiative in the U.S. to support power-building by community-based organizations to reverse deep-seated park and green space inequities in communities of color across the country.

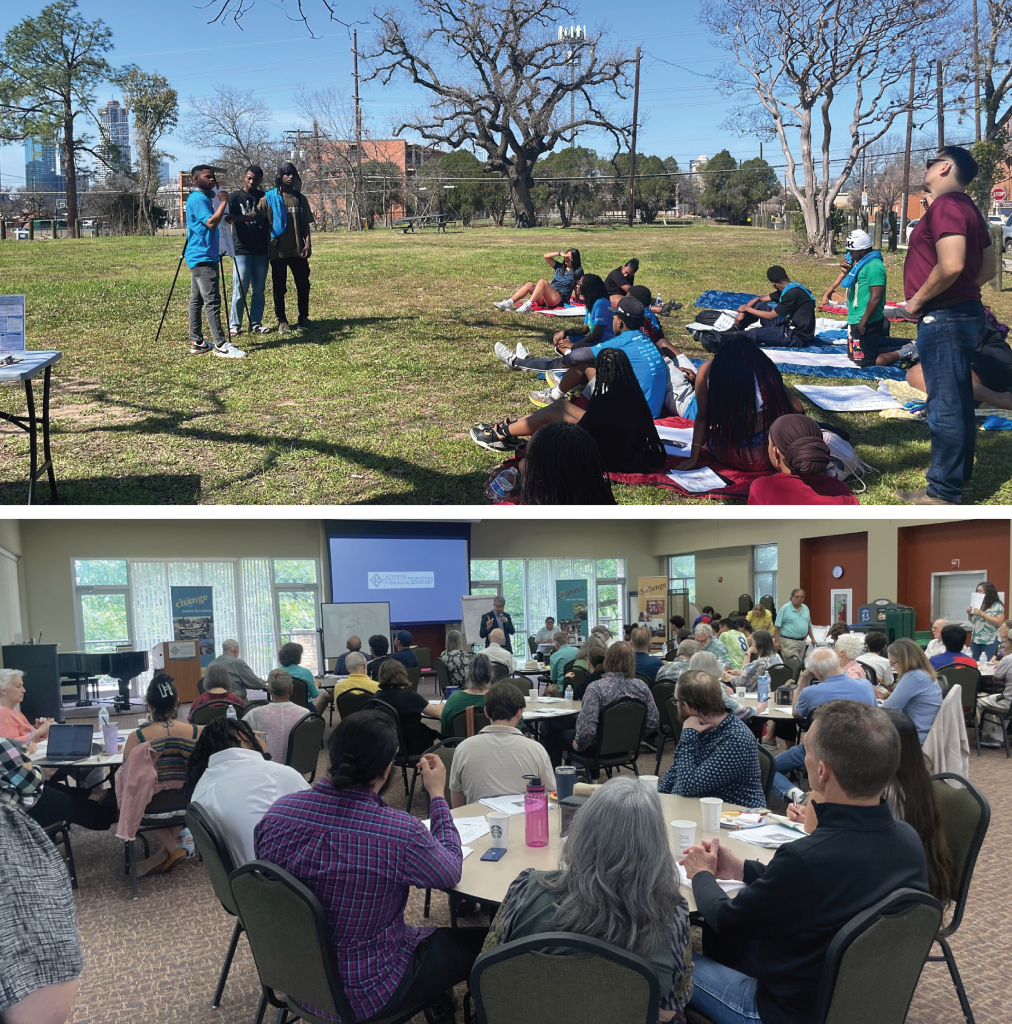

Photos of a group of students, faculty, and CTI members discussing pocket park plans outdoors.

We began establishing relationships with our neighbors at Austin Parks and Recreation by setting up meetings to engage with them, learn from them, and have our leaders share stories so they might also learn from us. We found partners in our school district and with the Cities Connecting Children to Nature Initiative. Our leaders educated themselves on our parks system and the history of our city that created it. They gathered within the community to learn about how folks in our neighborhoods feel about their green spaces. While Austin is a green city with many options, we heard that lots of people couldn’t always get to bigger parks — and didn’t always feel like those spaces were really intended for them anyway.

We learned that our parks department has a goal of ensuring a green space within a 10-minute walk of every resident, and we liked that goal. So we turned to the community and said, Is this real for you? Do you see this? And what we often heard was, ‘Yeah, but what do you mean by green space? And what do you mean by park? I go to the space around my local elementary school, or this little green area that I take walks around.’ It turns out that these spaces were pocket parks, and they just didn’t know it. What those spaces looked like and how they were identified by the community were sometimes different than those on the west side of I-35. So we discussed those differences and began to brainstorm ways to narrow and then erase the gap.

Photos of Warinda speaking.

What’s been most rewarding about getting involved in this way?

We work with many people who are used to having negative experiences with power. They’ve seen it used against them and have felt helpless. Over the years, and particularly in this work, we focus on helping our community members develop a new relationship with power. They recognize that it doesn't have to be negative, and it doesn’t have to be one-sided. We’re intentional about providing a space in which our neighbors can discover their own voices and use them. They can meet power with their own power. We provide opportunities for our member institutions to negotiate effectively through the political process with public officials around issues of common concern.

Top to bottom: People sit and talk around a green space; a person speaks to an audience of community members outdoors.

What’s been particularly rewarding in our work around green spaces is seeing how our neighbors come into power and what they do with it. For example, CTI student leaders at Huston-Tillotson University — Austin’s oldest institution and proud HBCU — held house meetings on campus on the subject of Black men’s mental health. They listened to young men talk about how they loved their school in East Austin and felt safe on campus within the quad, but that as soon as they stepped outside the gates of the campus and hit the sidewalk in front of the university, they could immediately tell that they were seen as a threat to people around them — people who didn’t know anything about them. They yearned for a space outside, where they could just sit under a tree to do their calculus homework — or nothing at all — and be comfortable in their own skin without someone treating them as a potential criminal. They wanted to be out in nature and not in danger.

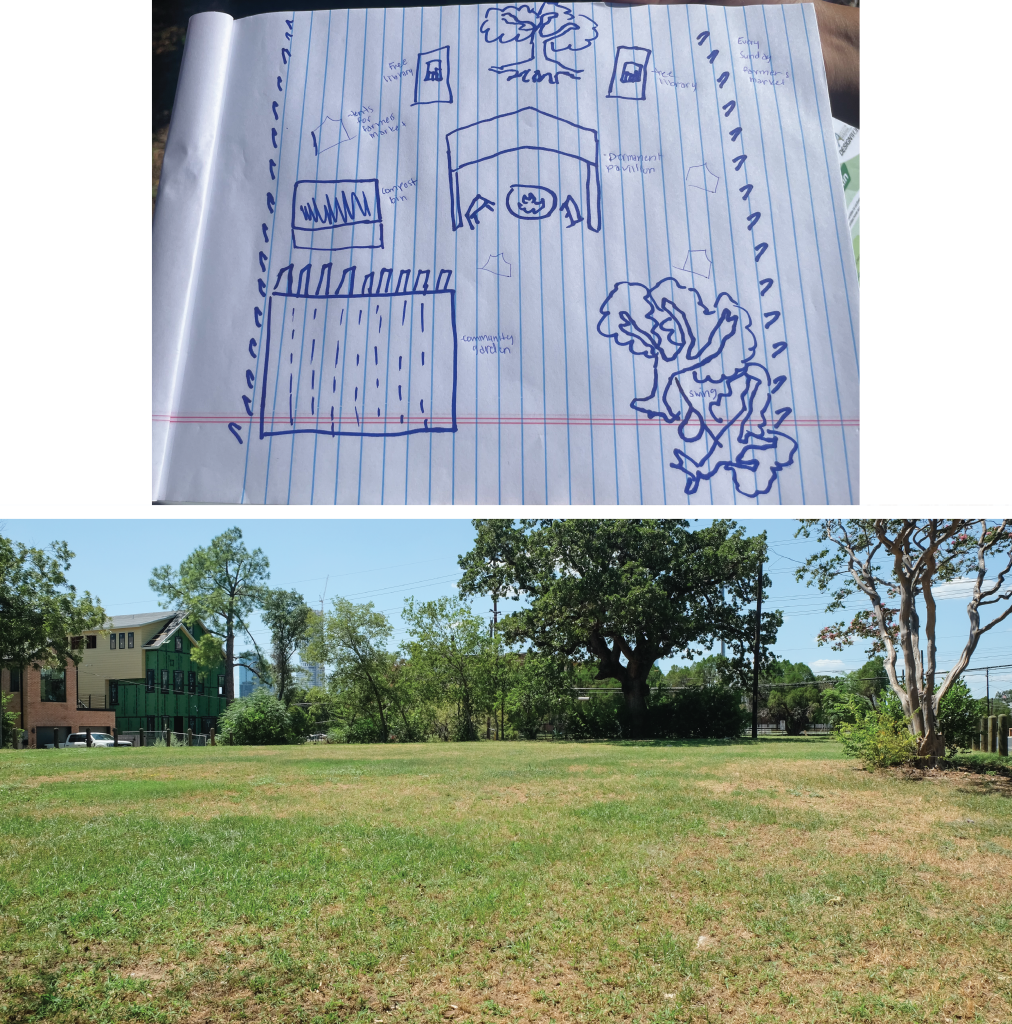

There happened to be a parcel of land across the street from Huston-Tillotson that appeared to be vacant, and when leaders inquired, they learned that it was actually owned by Austin Parks and Recreation. The leaders approached the parks department, and our neighbors there responded positively to the idea of students organizing a group to activate the space for use. In May 2024, CTI and Austin Parks and Recreation partnered on a grant proposal offered by landscape architectural firm Design Workshop.

Top to bottom: Warinda stands in the pocket park across from Huston-Tillotson; empty pocket park and site of the next park.

When the grant was awarded, students pulled community members into the park to speak directly with the parks department about what they wanted to see in this space. Student leaders worked with Austin Parks Foundation to host two well-attended It’s My Park Day events in Fall 2024 and Spring 2025. Their work resulted in the creation of a park activation toolkit that provides a reference for community members who want to activate parkland ahead of funding. They were so successful that Design Workshop’s non-profit arm, Design Workshop Foundation, selected the site as its Summer 2025 focus of the Charles Fountain Internship Project, bringing seven architectural students of color from around the country to provide programming options to the parks department for future funding. At the end of the summer, these interns handed their findings off to our student leaders to move the project forward. Huston-Tillotson professors are now creating a curriculum around student experiential learning at the site, focused on reaching out to the neighborhood around College Row to involve the community in activation and future programming. We’re enormously proud of these young leaders and their work.

Top to bottom: Students’ sketch of plans for pocket park space that include free library, tree library, pavilion, and other resources; empty green space and site for the future park.

What’s been the toughest part?

We’re living in a time during which, across the board, people feel that their institutions have let them down, and confidence in institutions — religious/civic/governmental — is at an all-time low. As our work focuses on building community power through institutions, it can sometimes be difficult to gain trust. But with patience and an eye toward long-term gain, we do it one conversation at a time, one house meeting at a time — developing leaders who want to act and who see the value of working with others for the common good.

Top to bottom: Students presenting and conversing in the empty pocket park; IAF West/SW National Co-Director Joe Rubio conducting training.

How do you help community members share their stories in a way that sparks action and policy change?

As we develop leaders, we also work with them to develop their personal stories — the stories that are unique to them, that have shaped them and their worldview, and that have caused them to act. We bring them into a community with other leaders who will be impacted by their stories and who have their own to share. The key is understanding that their stories are worth sharing, that no one can tell them like they can, and that by collective sharing with others, in conjunction with educating themselves on the issues, they can drive policy creation and change.

What advice do you have for others?

Practice having a conversation. People are struggling and are feeling alone. They want to connect with others but don’t know how to begin. Our advice: begin a conversation with someone in your circle of acquaintance who you want to know better. Begin with no expectation of solving a problem or being in agreement with them on anything other than that you want to know each other better. Then, listen more than you talk. Keep an open mind, and go where the conversation takes you. And if you find yourself thinking differently about something you’ve previously believed, take the opportunity to change your mind.

Is there a book, documentary, or other piece of media you would recommend for folks wanting to learn more about these topics?

- City in a Garden: Environmental Transformations and Racial Justice in Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas - by Andrew M. Bush

- City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways - by Megan Kimble

- The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America - by Richard Rothstein

- A City Plan for Austin, Texas (Austin’s 1928 master plan)

Warinda smiles in front of the empty pocket park.

Warinda’s work reminds us that equity and sustainability go hand in hand — and that meaningful climate action starts with listening, relationship building, and collective power. Through Central Texas Interfaith, she’s helping Austinites reclaim their voice in shaping greener, safer, and more inclusive neighborhoods, one conversation at a time. The transformation of spaces like the parkland across from Huston-Tillotson University shows what’s possible when community members lead and institutions show up to listen and collaborate.

The City of Austin shares the same commitment to community-led climate solutions through programs like the Austin Climate Equity Plan and initiatives such as Cities Connecting Children to Nature, the Bright Green Future Grants, and the Food and Climate Equity Grants — all of which empower residents to create lasting change in their own neighborhoods. Together, efforts like these continue to build a more resilient, equitable Austin.

To learn more about Austin's net-zero goal and the actions you can take to support a greener community, view the Austin Climate Equity Plan.

Share your Net-Zero contributions with us on X or Facebook, and use #NetZeroHero. If you know a Net-Zero Hero (or heroes!) who should be recognized for their efforts, send your nomination to climate@austintexas.gov.