The following is a discussion of policymaking processes utilized by other U.S. police departments.

In Phase I, OPO discussed APD’s ongoing contract with Lexipol—a private company that, among other things, provides services related to policy writing.[5] As outlined in the Phase I report, Lexipol prioritizes risk management for police departments and advertises itself as a way for police departments to decrease liability in civil suits alleging police misconduct.[6] This approach, however, does not necessarily result in policies that ensure accountability or reflect local community input.[7]

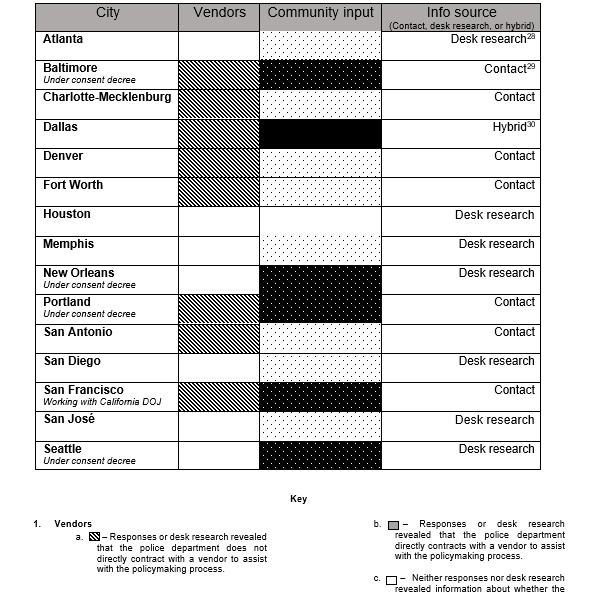

In Phase III, OPO wanted to learn whether comparable cities contract with Lexipol or other vendors to draft police policy, and the extent to which the police departments in these cities engage with the community as part of their policymaking processes. As a result, OPO reached out to police departments and oversight bodies in 15 cities across the country. OPO received responses from 8 cities, including:

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Francisco

For the 7 cities that did not provide a response, OPO conducted additional desk research to attempt to answer these questions. What follows are key findings from this 15-city survey:

1.None of the responding cities use vendors for policy writing.

OPO asked police departments and oversight bodies from 15 cities across the country about their use of vendors for policy writing and eight cities responded. None of these eight cities currently contract with vendors to write policy. The eight responding cities were as follows:

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Francisco

OPO conducted desk research on the seven other cities and did not find any information about whether they currently contract with vendors for policy writing. The seven other cities were as follows:

- Atlanta

- Houston

- Memphis

- New Orleans

- San Diego

- San José

- Seattle

- Vendor policies may indirectly impact cities that keep their policymaking processes in-house.

None of the responding cities currently contract with vendors to write policy, but several stated that they do things like:

- Solicit feedback from experts;

- Look at recommendations made by leading policing organizations; and

- Research policies and best practices of other police departments across the country.

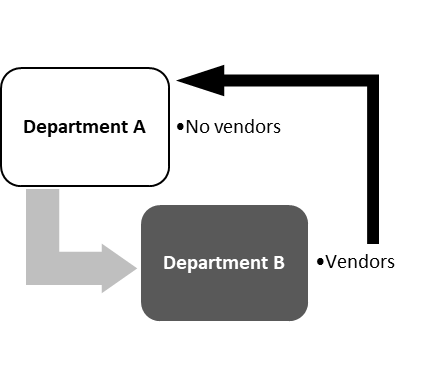

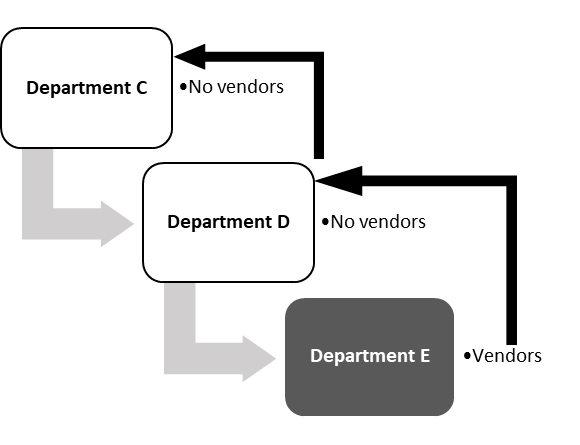

These practices are an established part of best practices research, but they make it nearly impossible to determine the degree to which vendors have input on police policy. Vendors can influence policy language even if they do not directly contract with a specific department. Consider the following scenarios:

- Department A does not contract with a vendor to write its policies. However, Department A examines Department B’s policies as part of its best practices research. Department B contracts with a vendor. Department A’s policies may be impacted by vendor-created language in Department B’s policies.

- Department C does not contract with a vendor to write its policies. However, Department C examines Department D’s policies as part of its best practices research. Department D does not contract with a vendor, but it does examine Department E’s policies. Department E contracts with a vendor. Department D’s policies may be impacted by vendor-created language and then impact Department C’s policies.

As these scenarios demonstrate, a vendor’s influence may reach beyond the contracting department. For example, a department that intentionally avoids policy vendors may end up unintentionally using vendor language based on the nature of their research process. OPO is aware of no comprehensive list of departments that contract with vendors to create policy, and research processes vary widely from department to department.

For example, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department reported examining specific cities that are relatively similar in population and department size.[8] On the other hand, the Baltimore Police Department reported reviewing various departments’ policies and best practices depending on the topic and recommendations made by stakeholders.[9]

Two cities (Baltimore and New Orleans) previously contracted with Lexipol for policy services.[10] Baltimore terminated their contract early as the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) came under a pattern-or-practice investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.[11] BPD has since secured staffing to support in-house policy development.[12] No policies developed by Lexipol were ever published by BPD.[13] New Orleans came under a pattern-or-practice investigation in May 2010,[14] and entered into a consent decree in January 2013.[15] New Orleans first contracted with Lexipol in December 2011 and extended their initial contract with Lexipol twice until 2014.[16]

Given the lack of response from New Orleans, OPO was unable to determine the extent to which the New Orleans Police Department utilized policies crafted by Lexipol.

In 2019, Lexipol reported providing policies to over 3,500 agencies.[17] Given this large number, it is impossible to ascertain whether Lexipol had a secondary impact on the police department policies of the 15 cities OPO surveyed. OPO was also unable to determine whether vendors other than Lexipol had a secondary impact. Nevertheless, the information that OPO did gather demonstrates that police departments appear to be able to keep up with current laws and draft comprehensive policies without relying on vendors.

3. Police departments use a range of methods to research best practices and collect community input, and the departments with more structured processes for community input take a multi-faceted approach that includes opportunities for both a broad response and a more focused response.

Approaches for collecting community feedback varied from department to department, differing both in frequency and process. For example:

- The Portland Police Bureau implemented a policy that requires it to regularly solicit community input and involves two public comment periods—one (15 days) for current language and another (30 days) for proposed changes made after meeting with subject matter experts and reviewing the initial public comments.[18]

- The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department only seeks community feedback in rare instances (e.g., revising its use-of-force policy after a 2019 officer-involved shooting).[19]

- The Denver Police Department solicits community feedback on policies that are considered major issues that impact community relations (e.g., policing technologies and the use of force).[20] In contrast, policies that are considered administrative in nature may only have input from other internal actors like elected officials and the city attorney’s office.[21]

- The San Francisco Police Department is implementing a policy that will require a 30-day comment period as part of the review process for most General Orders revisions.[22] Previously, the comment period was 10 days and community members had to present their feedback at a public meeting of the Police Commission.[23] The current process seeks feedback from community by directly involving external stakeholders through working groups dedicated to specific policies and significant collaboration with San Francisco’s civilian oversight office.[24]

- The City of Atlanta partnered with the Police Executive Research Forum and an Atlanta-based consulting firm in 2020 to assess the Atlanta Police Department’s policies and practices and gather community input.[25] The consulting firm unit engaged police, subject matter experts, and residents through town halls, focus groups, and surveys.[26] This resulted in a report with 150 recommendations, and a dashboard to track the implementation of recommendations that were approved.[27]

The way in which departments solicit community feedback also varied. Police departments’ processes usually included one or a combination of the following methods:

- Written response through email or an online portal;

- Partnering with external stakeholders (e.g., advocates and non-profit organizations);

- Organizing and overseeing working groups;

- Working with elected or appointed officials (e.g., mayors and public safety committee members); and

- Public community meetings or town hall events.

- Many oversight entities redirected questions about policymaking to their city’s police department, often citing a lack of detailed information.

OPO first contacted each of the 15 cities by reaching out to each city’s civilian oversight body. In many cases, the civilian oversight body redirected OPO to someone within the city’s police department, citing a lack of detailed information. This may suggest that current policymaking processes in these police departments lack transparency or that oversight bodies in these cities are not directly and routinely involved in the police departments’ policymaking processes.

The following table provides an overview of the information from each of the 15 cities, including the extent to which they utilize community input and vendors in crafting police department policy.