The Hybombacosm Experiment

A small-scale lake ecosystem, “microcosm” was designed to learn more about the growth of native cabomba and invasive hydrilla in Lake Austin and Lady Bird Lake.

Have you wondered why over a 13 year period Lake Austin would get choked with mats of the invasive exotic plant, hydrilla, yet Lady Bird Lake, just downstream, never experienced a hydrilla take-over?

Instead, what we have witnessed in Lady Bird Lake over the past five years is the growth of the native plant cabomba, notably between MoPac and the 1st St. Bridge.

Watershed Protection scientists wondered:

- Why doesn’t hydrilla grow in Lady Bird Lake?

- If Lady Bird Lake isn’t a good place for aquatic plants to grow then how can cabomba grow there?

- Can we improve Lake Austin habitat by growing cabomba in it?

In an effort to answer these questions, scientists created a “microcosm” (mini lake ecosystem) study by putting sediments and water from Lake Austin and Lady Bird Lake into buckets, planting either hydrilla or cabomba in these “mini-ecosystems”, and measuring plant growth for three months.

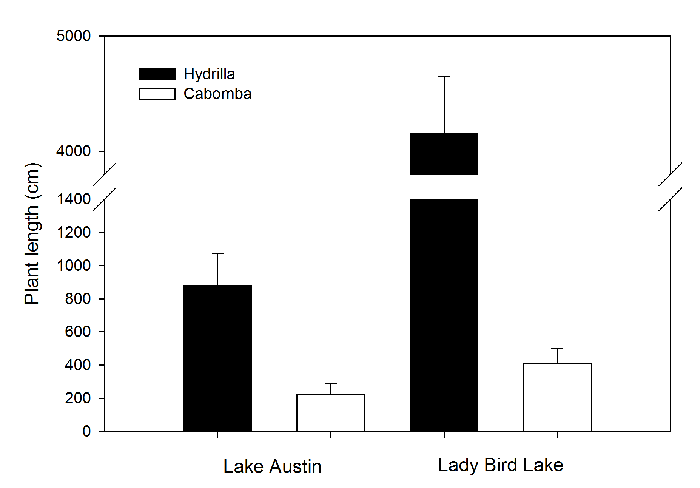

Scientists had their work cut out for them and had to change the water in the buckets each week with specific Lake Austin or Lady Bird Lake water. They also measured water nutrient chemistry and sediment texture to see if they could identify any differences between the reservoirs that might impact plant growth. Much to our scientists’ surprise, at the end of the experiment the greatest growth of hydrilla was in the Lady Bird Lake buckets! From our initial planting of 4 stems in each bucket totaling about 12” (yes, inches) in length, we ended up with over 130’ (yes, feet) of plant material in those little buckets after only three months!!!

Scientists had their work cut out for them and had to change the water in the buckets each week with specific Lake Austin or Lady Bird Lake water. They also measured water nutrient chemistry and sediment texture to see if they could identify any differences between the reservoirs that might impact plant growth. Much to our scientists’ surprise, at the end of the experiment the greatest growth of hydrilla was in the Lady Bird Lake buckets! From our initial planting of 4 stems in each bucket totaling about 12” (yes, inches) in length, we ended up with over 130’ (yes, feet) of plant material in those little buckets after only three months!!!

In the Lake Austin treatments we measured “only” 26’ of hydrilla growth at the end of the experiment. Here is an example of one clump of hydrilla from one of the buckets. And yes, we measured that entire thing, stem-by-stem.

So how did cabomba do in the Lake Austin buckets?

- Turns out, not as well as in the Lady Bird Lake buckets. We measured the shortest stems and the least amount of biomass for plants grown in the Lake Austin treatments.

- After three months, we measured a sparse 7’ of plant material, about half the growth observed for the Lady Bird Lake control treatment.

In terms of hydrilla, the nutrient-rich waters and sediments found in Lady Bird Lake really fueled tremendous and rapid growth. So why is hydrilla not all over in Lady Bird Lake? Our best guess is that all of the turtles, waterfowl, and carp (all herbivores) in the reservoir like to eat hydrilla. In fact, aside from Cabomba, we cannot get much aquatic vegetation to grow outside of cages in Lady Bird Lake because of herbivores.

One of our aquatic plant cages in Lady Bird Lake

Apparently, there is something about the cabomba that makes the plant undesireable to herbivores. Literature suggests perhaps chemical defenses, poor food quality, or it is just simply not tasty. Cabomba also appears to be very particular about where it likes to grow preferring the soft, silty, nutrient-rich sediments, and less basic pH waters that are in Lady Bird Lake. Lake Austin has sandy sediments, a higher pH, and lower nutrient concentrations which appeared to slow down plant growth. As such, while cabomba may be able to colonize some portions of Lake Austin, from our initial results we do not think cabomba would grow at a rate that would compete with hydrilla.

So, the next time you are kayaking or paddle-boarding on Lady Bird Lake, be sure to give thanks to all those turtles, birds, and fish you see for the important work they do.

For more information about Austin’s lakes visit www.austintexas.gov/austinlakes