Isamu Taniguchi

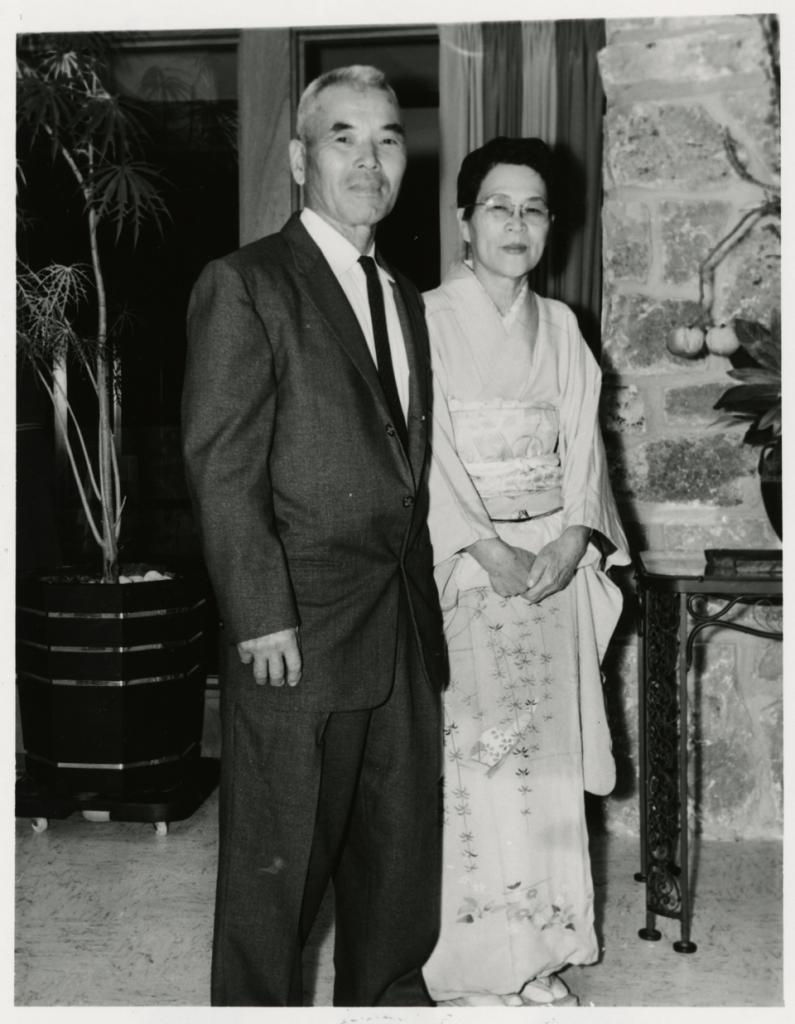

Born in Osaka, Japan, Isamu Taniguchi immigrated to the United States in 1914 at the age of sixteen, only returning to Japan to marry Sadayo Miyagi and bring her back to the US.

Initially unable to own land, due to the state law in California prohibiting him due to his ancestry, he created a life for his family near Stockton. He spent twenty-two years farming and established a local farming cooperative called the Brentwood Produce Association, a group that organized the shipping of various crops all over California and to the East Coast.

Photo courtesy of the Austin History Center PICB-1211

This lasted until the executive order President Roosevelt issued that authorized the evacuation and relocation of all persons deemed a threat to national security after the US entered WWII. In March of 1942 Isamu was arrested and was accused of using the incinerator on his land to send smoke signals to the Japanese and of arranging muslin sheets (used to protect tomato plants from the spring frost) in arrow shapes that supposedly pointed to military installations. Though not officially charged with anything, he was deemed a dangerous enemy alien and he, his wife, and his younger son, Izumi, were sent to the Crystal City Internment Camp in South Texas - his older son, Alan, was away at university and was not arrested with the rest of the family.

While in Crystal City, Isamu worked for the carpentry shop and in his spare time he planted and maintained gardens. These activities kept him busy, but didn’t distract from the situation. Communicating with the outside world was limited as internees were limited to writing two letters and one postcard per week and censors read incoming mail, cutting out anything that had to do with the war. Even comic books were confiscated out of concern for coded messages.

When news came of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki many believed it to be propaganda as it was thought impossible that Japan had lost the war, and while he believed the news, Isamu continued to tend the gardens and his bonsai. “It was like watching the world come to an end,” he later wrote in an essay. “The radiation from atomic bombs, which started from Pika-don [the flash and sound of an explosion] over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, shines in every corner of our skulls, analyzing right and wrong, flying over our heads with the humming sound, becoming a god-whip to kill instantly, pressing us to act in repentance.”

When they were eventually released from Crystal City, Isamu and Sadayo hoped to begin their lives again in California. Unfortunately, there was still a great deal of hostility from local people who did not want anyone associated with “the enemy” living nearby, and this included Isamu and his family.

So they instead decided to go to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Many of the Japanese farmers they had met while imprisoned had settled in this area, and had invited the family to join them there. Finding it to be much more welcoming than their old home in California, Isamu and Sadayo established a large vegetable and cotton farm and remained there until they retired in 1967 when they moved to Austin to be near their son, Alan, a professor of architecture at the University of Texas.

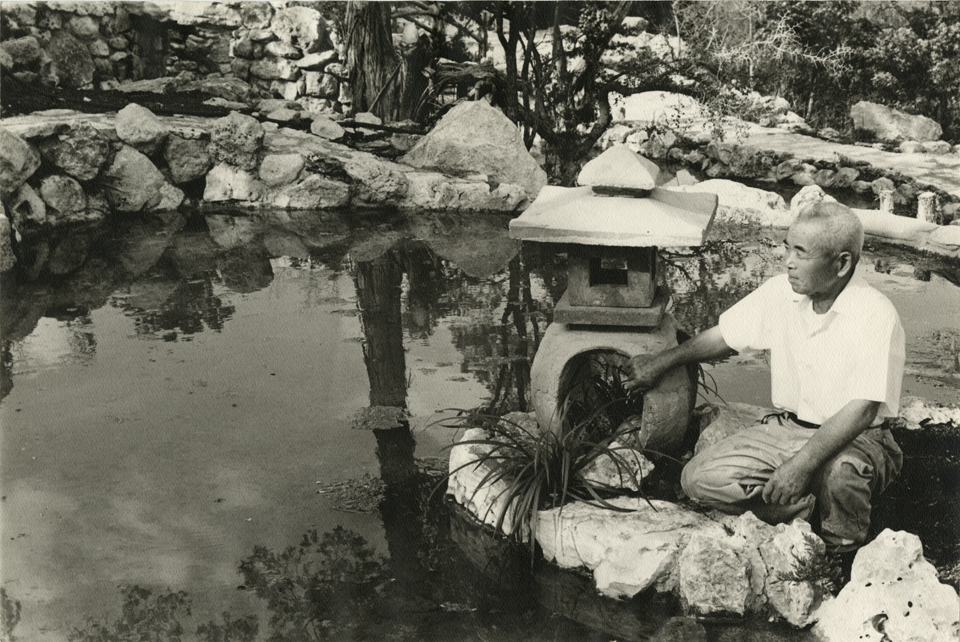

Photo Courtesy of the Austin History Center PICA-25667

After moving, Isamu expressed a desire to build a Japanese garden dedicated to peace that would be open to visitors and the public, and he hoped Alan would help him find a location. Alan had made good connections with the City of Austin Parks and Recreation Department, and the director suggested three acres of land that were part of Zilker Park. Isamu worked almost entirely on his own, without a contract, salary, or written plan to transform this space with intricate pathways, a miniature waterfall, ponds, stone arrangements, and lush plant-life (one pond even has a lotus he raised from a seed from Japan).

Photo courtesy of the Austin History Center PICB-13330

Today, the Taniguchi Japanese Garden serves as an enduring symbol of peace and has 100,000 visitors every year. Inscribed on a plaque inside the garden’s teahouse are the words “When a man with such pure appreciation in his peaceful mind, tries to compose with stones, grass, and water in order to create one unified beauty—the formation is called a ‘garden.’ . . . It has been my wish that through the construction of this visible garden, I might provide a symbol of universal peace.”

Isamu Taniguchi passed in 1992 after suffering from a stroke in 1990 and is buried next to his wife in Austin Memorial Park Cemetery.