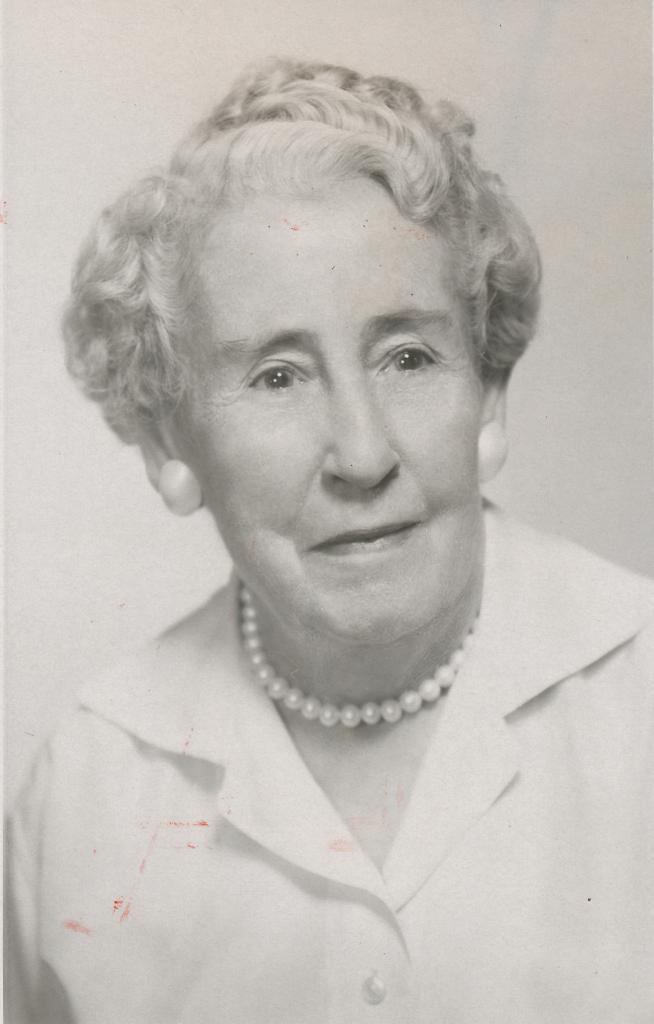

A devoted elementary school teacher who would eventually have an elementary school named after her, Lalla Odom was born in 1874 and earned her B.A. degree at the age of seventeen in 1891. She continued her education at Waco Female College and Baylor University before she enrolled in the Conservatory of Music in Cincinnati. Her degree from the Conservatory led directly to a position as a teacher of music and mathematics at Willie Halsell College in Vineta, Oklahoma.

After meeting and marrying her husband, Edgar Odom, they moved around and lived all ove…

Karl Downs was an influential minister and educator who affected the lives of many children and young adults in his work with his community, his church, and as president of Samuel Huston College.

With degrees from Samuel Huston College (now Huston-Tillotson College); Gammon Theological Seminary in Atlanta, Georgia; and from Boston University. He later received an honorary doctor of divinity degree from Gammon Theological Seminary, and at the time of his death he was a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern California.

Portr…

Joe Sing had many names in his life. He was born Jo Feng Sheng in China in 1860 and when he came to the United States to find work he became known as Jo Sing. In New Orleans he worked under the name of Joe Hall. Then in Austin, he was known to his customers as Hong Lee.

According to the U.S.census he was in Galveston in 1880 before spending some time in Boston, MA, as well as Shreveport, LA. And in 1894 he was issued a certificate of residence in New Orleans (a document required for a Chinese national to work).

…

Dr. John Quill Taylor King, Sr. was initially born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1921.

After his mother remarried following his father’s passing in 1923, his family moved to Austin and opened the King Funeral Home, which was later merged with the Tears Mortuary in 1955.

…

Zachary Thomson Scott was born in December 1880, in Fort Worth, Texas and grew up on his family’s ranch in Bosque County, Texas. He attended a private school near Fredericksburg, Virginia and was taught by his aunts, returning to Texas to attend the University of Texas medical school in Galveston.

As he was living in Galveston at the time of the 1900 hurricane, he was actively involved in rescuing the many patients that were trapped by the floods.

After graduating in 1903 he began his practice in Clifton, Bosque County, but moved to Austin in 1909. He established the Austin Sanitarium with Thomas J. Bennett where he developed a life-long professional interest in Texas…

Pauline Lynch Evans Creighton was born on May 18, 1868 in Clay County, Mississippi to Hettie M. Cochran Lynch and Judge James Daniel Lynch. Little is known about Pauline's life during and after her two years of college, but it is believed that she married H. L. Evans. Together, they had a son, Hugh McCord Evans on March 12,1891.

Pauline's parents moved to Austin, Texas in 1884 and Pauline and her son joined them some time after. It is not known what happened to her first husband, but Pauline married John Orde Creighton in 1901. The couple welcomed their first child together, a son named John Orde Creighton, Jr.

Pauline was active in local city improv…

Hart Stilwell was born in 1902 in Yoakum, Texas. When he was two, his large family relocated to the Rio Grande Valley. His life growing up pretty chaotic and there was a lot of conflict with his father, a former Texas Ranger with anger issues who was prone to mood-swings and threats of violence.

At seventeen Stilwell began studying at the University of Texas and worked for The Daily Texan, graduating with a degree in journalism in 1924. In 1925 he married Mary Gray Seabury. After graduating he became a reporter for The Brownsville Herald and later served as their editor. In the later 1920s Stilwell shifted his attention to free-lance writing while continuing to contribute articles…

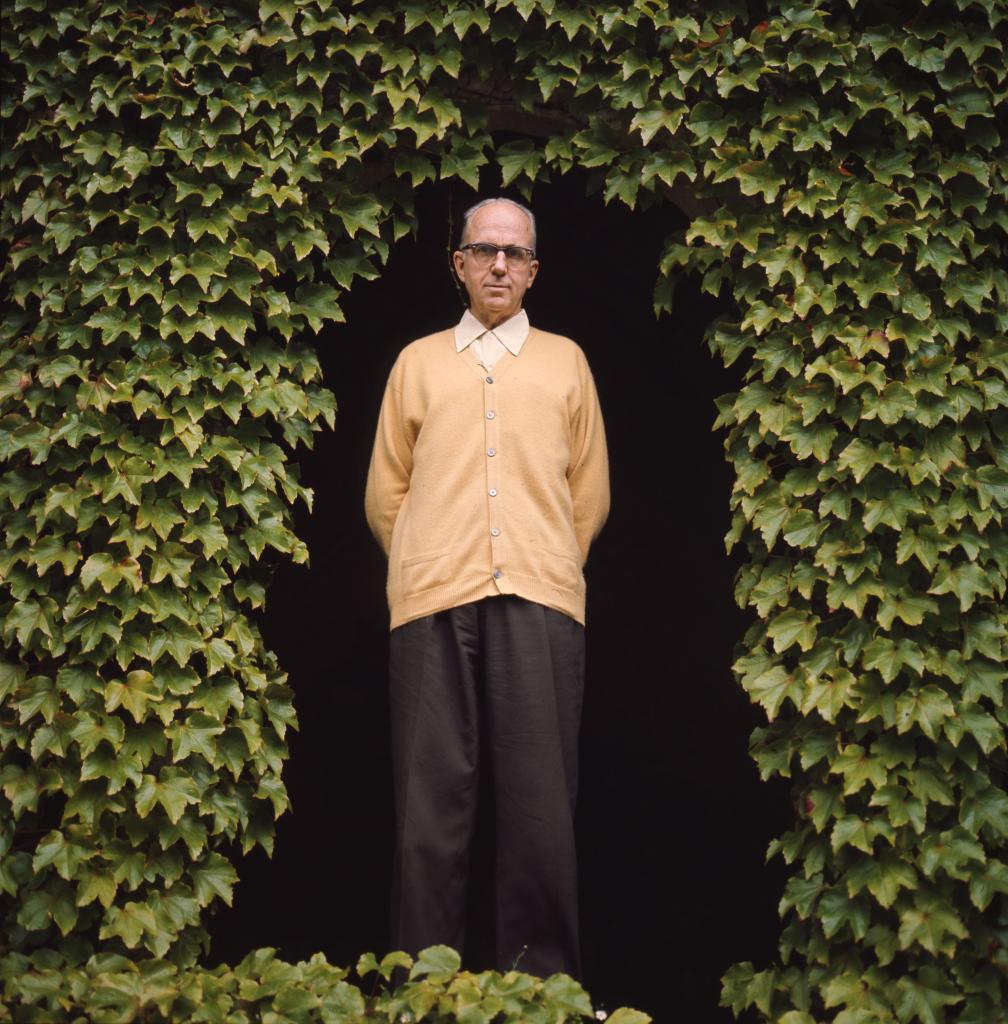

James A. Michener was born in NYC in 1907, but never knew who his birth parents were. As a foundling he was adopted by Mabel Michener and raised as a Quaker. In his teens he hitchhiked and traveled by boxcar all across the US gaining life experiences that fed into his later writing. After graduating from Swarthmore College summa cum laude he became a teacher. He began his writing career with articles on teaching social studies published between 1936 and 1942.

Image Court…

Día de los Muertos has become a popular holiday held throughout major cities in the United States. It’s an event that is still mysterious and misunderstood by many. But in Mexico, it’s a holiday that is rooted in Mesoamerican mythology and Catholic beliefs of Spain.

The days identified with Día de los Muertos are from October 27 – November 2, when the living remember their loved ones by cooking special foods, decorating altars, and providing offerings for those deceased. In indigenous rural regions in Mexico, families and communities gather together for a procession to th…

.JPG)